Laud was the Protestant Archbishop of Canterbury under Charles I of England. He belonged to that generation which was born somewhat before the year 1600 and which was old by the middle of the seventeenth century — that is, by the time that each party in the great religious quarrel of the Reformation was dimly appreciating that the battle was a drawn one, and that there could not be a complete victory on either side.

It will be remembered that the middle of the seventeenth

century, and more particularly the date 1648 (The Treaties

of Westphalia), marks that moment of exhaustion on the

two sides. After it, what used to be united Christendom was

permanently divided into the two camps of the Catholic

and Protestant cultures, the boundaries of which have not

appreciably changed from that day to this. Laud, as Archbishop of Canterbury, was the principal figure in English

official Protestantism; that is, in the new establishment set

up by William Cecil, and known as "The Church of England" in the critical period when the conflict was being

decided. He was put to death by the English revolutionaries

a little before the general settlement just mentioned; and he

had begun his characteristic activities less than twenty years

after the beginning of the century.

His personality is most interesting. He was of the middle

ranks of society, with no special advantages of birth, and

gained public attention wholly through his own energy and

character. That energy was intense and never failed him

to the end; it was as great in his last days as in his first

and it animated a very small body — for he was almost a

dwarf in size. His volume of work and correspondence was

enormous, his power of attention to detail was equally great,

and he followed a fixed clear policy with great chances of success, which was only defeated by the rise of a general rebellion against the English Royal Government, in which

his own activities and office were included.

And the issue is of course, the authority of the Pope. Belloc notes that Laud and others wanted Christian unity but could not accept one authority in the Church: the Vicar of Christ (whom they thought of as "an Italian priest" at worst, the bishop of Rome at best):

They inclined (as their descendants, the High Churchmen, do to-day) to an explanation of the mystery of the Eucharist more and more approximating to the truth. They inclined to Sacramental Penance and the Sacramental view of religion in general. They were particularly strong upon the necessity of a hierarchy and upon what they hoped was in their own case and what they admitted in the case of Catholics to be, the Apostolic Succession. They desired to regard their clergy as priests and some of them indeed would come to say even "sacrificing priests." But with all this they remained Protestant. They remained (though they would not have admitted it) thoroughly anti-Catholic, because they rejected that one part of Catholic doctrine which is its essential — the combination of unity and authority. The unity of the visible Church and its invincible authority were repugnant to their growing nationalism, and those who preserved such an attitude of mind were just as much the enemies of Catholicism as the most rabid Puritan could be, or the most complete agnostic.

Laud himself used a phrase which has become famous in this regard: he said that he could not consider reunion "with Rome as she now is." Now that phrase was not only a rejection of unity, but by its wording it implied that there was no united visible Church of God on earth. The use of the word "Rome*' in this connection emphasized and was intended to emphasize the doctrine that "the Church of Rome hath erred" — which inevitably includes the doctrine that "all the Churches [as the phrase goes] had erred"; and that therefore there was no united visible infallible Church.

Analyzing Laud's legacy after his execution by Parliament, Belloc comments:

But the legacy of Laud in ecclesiastical matters had more vitality. It fell very low during the eighteenth century, but it was revived before the end of that century . . . There followed, in the same lifetime, the Tractarian Movement, and there now exists in greater force than has hitherto been known, a Laudian spirit acting in varying degrees throughout one great section of the English Protestant Establishment. The more devoted followers of that spirit go far beyond Laud himself in their imitation of Catholicism, and even in the attempt to recover the spirit of that from which they are separated; a considerable minority express themselves openly in favour of that reunion with the Catholic Church which Laud himself rejected.

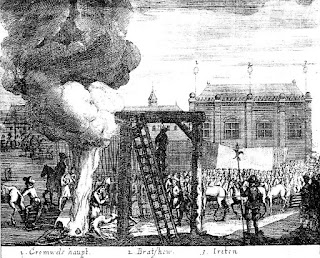

Then Belloc turns to Oliver Cromwell, military leader, regicide, and Lord Protector. Like St. Thomas More and Thomas Cromwell before them, William Laud and Oliver Cromwell have something in common: they both lost their heads. The timing was just different! Cromwell's body was exhumed during the reign of Charles II and he was "executed". His head was displayed on a pole in front of Westminster Hall until 1685 (Charles II's father had been tried by Parliament in Westminster Hall.)

After reviewing the religious doctrines of Calvinism, Belloc comments on Cromwell and his Puritanism:

Puritanism is a particular form and degree of Protestantism which has specially flourished in England, Scotland and Wales, but of which there were wide areas throughout the Protestant world, notably in Scandinavia and in Holland. To be a Puritan is almost exactly the same as to be what the old world used to call a Manichaean. The Puritan and the Manichee have the same attitude towards the universe; their creeds work out to the same moral and social practice. But there is one doctrinal difference between them, for while the Manichee believes in an evil principle which works side by side with and is equal to the principle of good in the universe, the Puritan, proceeding from Calvin and therefore only admitting one will in the universe, makes both evil and good combine in the same awful God who permits, and in a sense wills, evil, and particularly the sufferings of man.

Belloc picks up his common theme, that the English Reformation had led to the creation of new wealth:

The accidents by which Oliver Cromwell became the typical figure of English Protestantism in its extreme or Puritanical form were these:

He was a cadet of one of those millionaire families who had gained their enormous wealth out of the wreck of the monasteries during the period of the Reformation. His father, of whom he was the only surviving son, was himself the only son of the enormously wealthy Sir Henry Cromwell, and Henry was the son of Richard Cromwell, nephew of Thomas Cromwell, the man who dissolved the monasteries under Henry VIII. Richard Cromwell's real name was Richard Williams. He was nephew to Thomas because his mother had been Thomas Cromwell's sister, his mother having married a tavern-keeper in Putney, near London, whose name was Williams. Richard took on his important relative's name, but both he and those who succeeded him had to use the name Williams for legal purposes, and when his great-grandson, Oliver, lay in state, the title "Oliver Cromwell, alias Williams," was embroidered on the half- royal hangings which draped the bed. . . .

Nevertheless, Cromwell's success and his Protectorate were decisive in the process of establishing Protestantism in England:

Those who retained Catholic principles and inclinations in England were still very numerous; when he died they were still more than a quarter of the population. In Ireland, in spite of massacre and wholesale robbery the great Catholic mass stood firm, and there at least seven-eighths of the people retained their religion in spite of the conquest; but the Civil War had completed both in Britain and in Ireland that long process of Catholic impoverishment and Protestant enrichment which had begun with the Dissolution of the Monasteries more than a hundred years before and had been continued with the Irish confiscations under Elizabeth and completed with the enormous fines levied upon all those landowners in England who stood out boldly and openly proclaimed themselves Catholic.

Further, the victory of those for whom Cromwell stood and of whom he was the most conspicuous leader was the virtual end of the monarchy, although kingship had come back amid universal rejoicing before young Charles had been crowned at Westminster and all the rest of it. The great landowners and the great merchants, acting through the House of Commons and the House of Lords, which they formed, took over the government in England and have retained it ever since. Further, after that episode there could be no question of the Catholic Faith returning in any strength. It might have survived in a large fraction of the people, but it could never again mould the general spirit of England.

Oliver Cromwell, therefore, is not only the chief Puritan figure at the decisive moment, the seventeenth century, when the Protestant and Catholic separated finally and agreed to call it a drawn battle; he is also the figure who marks the turning point in the transformation of England from a Catholic to a Protestant country. The process was not completed under him. Catholicism largely survived in England till it received its death blow there in 1688. But by the time of his death the Protestant character of England as a whole was firmly fixed.